A few years ago when I was into reverse engineering and binary analysis (and game modding), I did a lot of research into anticheats work. I was curious about tracking their updates, since that would allow me to:

- Know when a new version is released

- Understand what changes were made

- Use older versions for research purposes

So I ended up researching different ways on how to track updates of various anticheats. Some of them are already very well documented, while others haven't been explored much. This post will summarize my findings and outline how they work.

EasyAntiCheat

EasyAntiCheat is widely recognized as one of the most advanced anticheats, and is used in many popular games like Rust, Fortnite, Apex Legends, and more.

Prior to the acquisition by Epic Games, EAC was using their own CDN to distribute updates: https://download.eac-cdn.com/api/v1/games/{game_id}/client/{system}/download/?uuid=1239688.

game_id: unique identifier for each game (e.g. 154 for Apex Legends)system: target platform/system (e.g.wow64_win64,mac64,linux32_64).

After the acquisition, they switched to the EpicGames CDN, which has a slightly different URL structure: https://modules-cdn.eac-prod.on.epicgames.com/modules/{product_id}/{deployment_id}/{system}. The parameters to this URL are completely different:

product_id: unique identifier for each game (e.g.429c2212ad284866aee071454c2125b5for Rust)deployment_id: unique identifier for each deployment (e.g.76796531e86443548754600511f42e9efor Rust). This doesn't change when an update is released and is used to identify different game versions.system: same as in the old CDN

After downloading the module for a game, we'll have a file which contains data with a very high entropy which is the first indication that it is encrypted or compressed:

$ bat encrypted.bin | ent

Entropy = 7.989390 bits per byte.

Looking at the data, we also can't really identify any patterns or strings. However, across versions the header seems to always stay the same (a7 ed): Very interesting 🤔

$ hexyl encrypted.bin | head

┌────────┬─────────────────────────┬─────────────────────────┬────────┬────────┐

│00000000│ a7 ed 96 0c 0f 0f 12 19 ┊ 1c 1b 1e 20 22 26 2a e5 │×××_••••┊••• "&*×│

│00000010│ e8 33 36 39 3c 3f 42 85 ┊ 88 4b 4e 51 54 57 5a 5d │×369<?B×┊×KNQTWZ]│

│00000020│ 60 63 66 69 6c 6f 72 75 ┊ 78 7b 7e 81 84 87 8a 8d │`cfiloru┊x{~×××××│

│00000030│ 90 93 96 99 9c 9f a2 a5 ┊ a8 ab ae 31 34 b7 ba cb │××××××××┊×××14×××│

│00000040│ ed 9c 8e d7 80 8c a8 c3 ┊ b1 94 2b fa d2 5c a6 be │××××××××┊××+××\××│

│00000050│ cc 86 86 db dd d5 db d8 ┊ d6 98 91 d5 e3 f3 f7 00 │××××××××┊×××××××⋄│

│00000060│ b4 a5 ed ae be 16 15 c3 ┊ c1 12 cc a5 d7 e9 bd da │××××ו•×┊ו××××××│

│00000070│ 2c 26 1f ec 97 79 79 93 ┊ 8c 6b 6e 71 74 77 7a cd │,&•××yy×┊×knqtwz×│

│00000080│ 15 c8 86 d5 d9 93 95 c9 ┊ 4d 6e 58 09 a4 a7 aa ad │•×××××××┊MnX_××××│

A few years ago, I spent a night early morning with a friend to find the decryption algorithm. We searched for anything that closely resembled such an algorithm, eventually found it, made a quick POC and got it working 🔥. Here's what the code looks like:

void

After decrypting the binary blob, we'll finally have a PE image (EasyAnticheat.packed.dll):

$ hexyl EasyAnticheat.packed.dll | head

┌────────┬─────────────────────────┬─────────────────────────┬────────┬────────┐

│00000000│ 4d 5a 90 00 03 00 00 00 ┊ 04 00 00 00 ff ff 00 00 │MZ×.•...┊•...××..│

│00000010│ b8 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ┊ 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 │×.......┊@.......│

│00000020│ 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ┊ 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 │........┊........│

│00000030│ 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ┊ 00 00 00 00 80 00 00 00 │........┊....×...│

│00000040│ 0e 1f ba 0e 00 b4 09 cd ┊ 21 b8 01 4c cd 21 54 68 │••×•.×_×┊!וL×!Th│

│00000050│ 69 73 20 70 72 6f 67 72 ┊ 61 6d 20 63 61 6e 6e 6f │is progr┊am canno│

│00000060│ 74 20 62 65 20 72 75 6e ┊ 20 69 6e 20 44 4f 53 20 │t be run┊ in DOS │

│00000070│ 6d 6f 64 65 2e 0d 0d 0a ┊ 24 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 │mode.___┊$.......│

│00000080│ 50 45 00 00 4c 01 03 00 ┊ 34 81 52 68 00 00 00 00 │PE..L••.┊4×Rh....│

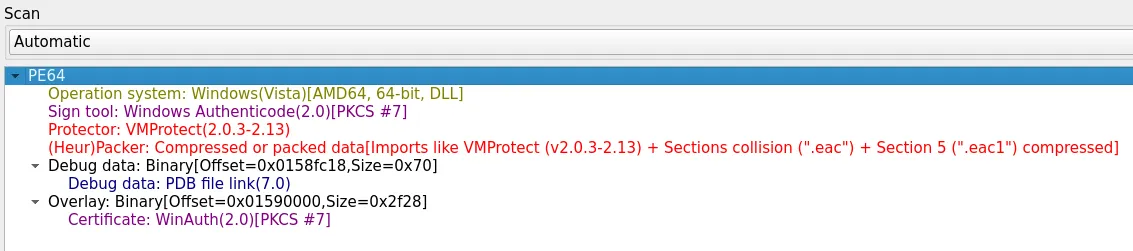

Unfortunately, we're not yet done. According to Detect it Easy, the binary is protected with VMProtect, which means we can't just read the .text or .data section. However, to further analyze the binary and extract the driver and usermode module we'll have to find a way to unpack it.

There are many ways to unpack binaries, with the most popular being emulation and native execution. Both methods just execute the entrypoint until the sections are unpacked. In our case, the easiest way to unpack the downloaded binary is to load it with LoadLibraryA:

use ;

use PeView;

use PathBuf;

After analyzing this unpacked library, you'll eventually figure out that the .data section has a high entropy and is quite large. You might even recognize the encrypted PE headers from earlier: a7 ed. This is exactly where the driver and their internal module are stored.

The embedded files use the same encryption algorithm, so we can search for the encrypted PE header (MZ or 0x4D5A). After looking at the data in IDA, I managed to find a pattern which we can use to extract the embedded files. The encrypted modules are always stored in the following order:

<encrypted_module> (encrypted data)

<size> (padded to 16 bytes)

This is somewhat equivalent to the following structure, where len always contains the size of the buffer:

By knowing that the encrypted module has a high entropy, which means that it's very unlikely that there will be patterns in the data, we can simply search for at least 8 bytes of zero padding which is always present after the size.

let section = pe.section_by_name;

let = section.find_padding_at;

let encrypted_driver = section;

let driver_module = decrypt;

assert_eq!;

let = section.find_padding_at;

let encrypted_internal = section;

let internal_module = decrypt;

assert_eq!;

Battleye

Battleye, another popular anticheat from Germany, is known for its bandaid fixes and lack of security. They put a lot of focus on detecting popular cheat providers, by detecting them via static signatures. It is used in games like Arma, DayZ, Escape from Tarkov, and most recently Grand Theft Auto V.

Their CDN seems to be built in-house and follows a very simple structure:

- Fetch the latest version (which is just a unix timestamp like

1746714230) - Download the module using the version number from the actual CDN

Here are the required URLs:

- Version URL:

https://cdn.battleye.com/{game}/ver - Download URL:

https://cdn.battleye.com/{game}/{version} - Possible values for the games include:

eft,unturned,ark,r6s/win-x64,dayz/win-x64.

The downloaded binary contains other bytes before the actual module, which have to be filtered out. The easiest way to do it is to search for the PE header and delete everything before. In this case, the PE module is located at offset 0x200:

$ binwalk 1732793154

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

512 0x200 Windows PE binary, machine type: Intel x86-64

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The downloaded file is BEService.exe, which also embeds their kernel driver which is extracted when the service is started. You can use the same techniques as with EAC to extract it, so I won't go into further details.

Electronic Arts Anti-Cheat (EA-AC)

EA-AC (not to confuse with EAC) is a relatively new anticheat that was launched in 2022. It is used in games like FIFA or Battlefield, which all use the same installer. The direct download link to their installer can be found on the help.ea.com page which links to the following URL: https://cdn.eaanticheat.ac.ea.com/EAAntiCheat.Installer.exe.

Instead of having to run the installer, we can simply usage 7z to extract the contents. However, they are not shipping the driver with the installer anymore, so you need to dump it while running the game or reverse engineer the download.

$ 7z l EAAntiCheat.Installer.exe

Date Time Attr Size Compressed Name

------------------- ----- ------------ ------------ ------------------------

2025-06-14 08:03:50 ..... 44388600 26865015 ProgramFiles/EAAntiCheat.GameService.dll

2025-06-14 08:03:36 ..... 116300024 108845059 ProgramFiles/EAAntiCheat.GameService.exe

2025-06-14 08:04:12 ..... 26872 14232 ProgramFiles/preloader_s.dll

2025-06-14 08:03:50 ..... 37148408 20349480 Title/EAAntiCheat.GameServiceLauncher.dll

2025-06-14 08:03:50 ..... 15922936 13955947 Title/EAAntiCheat.GameServiceLauncher.exe

2025-06-14 08:04:12 ..... 27384 14245 Title/preloader_l.dll

------------------- ----- ------------ ------------ ------------------------

2025-06-14 08:04:12 213814224 170043978 6 files

Vanguard

Vanguard is the anticheat used in Valorant and League of Legends, developed by Riot Games.

Despite their advanced security features, is is relatively easy to track the updates. They provide a public API to fetch the latest config which includes the version and URL for the anticheats modules: https://clientconfig.rpg.riotgames.com/api/v1/config/public

{

"anticheat.vanguard.backgroundInstall": false,

"anticheat.vanguard.enabled": true,

"anticheat.vanguard.enforceExactVersionMatching": false,

"anticheat.vanguard.steppingStones": [

"1.16.15.9"

],

"anticheat.vanguard.url": "https://riot-client.secure.dyn.riotcdn.net/channels/public/rccontent/vanguard/{version}/setup.exe",

"anticheat.vanguard.version": "1.17.6.2",

...

}

After downloading the files from the CDN and extracting them (again either via 7z or by running the installer), we'll have the following files. This already includes the driver and usermode components, so we don't even have to extract anything.

$ 7z l setup.exe

Date Time Attr Size Compressed Name

------------------- ----- ------------ ------------ ------------------------

2025-05-05 20:43:53 ....A 21651 6298 vgc.ico

2025-05-05 20:54:45 ....A 4494048 55866276 installer.exe

2025-05-05 20:57:34 ....A 4285400 log-uploader.exe

2025-05-05 20:55:20 ....A 40075376 vgc.exe

2025-05-05 14:18:24 ..... 26955888 vgk.sys

2025-05-05 20:55:53 ....A 10524776 vgm.exe

2025-05-05 20:56:48 ....A 3239456 vgrl.dll

2025-05-05 20:57:10 ....A 4143376 vgtray.exe

------------------- ----- ------------ ------------ ------------------------

2025-05-05 20:57:34 93739971 55872574 8 files

Conclusion

It's surprising to see the differences in CDNs for different anticheats. You might think, why don't all anticheats have a state-of-the-art military-grade quantum-proof AI encrypted CDN™: Turns out it doesn't matter if people can extract all of the anticheat modules or figure out when the anticheat updates.

At best, it makes it a little bit more inconvenient or time consuming for researchers (which is pretty much the whole purpose of an anticheat). The main purpose is to protect the games and this is done by protecting the modules that do the detections rather than the CDN.

I worked on this project a few years ago, even gave a talk at a local meetup about the architecture, but never got around to publish a blog post about the internals. I really enjoyed working on this project, trying out new tech stack and learning about devops, deployment, object storage (MinIO) and a lot more. While some of the information likely is not unknown anymore, I still hope you learned something.

Appendix

EQU8

EDIT: Turns out the CDN doesn't work anymore, but I wanted to include it for the sake of completeness

EQU8 is an anticheat developed primarily for the game Splitgate. It isn't as advanced as the previously mentioned anticheats, but still provides some level of protection against cheaters.

The download URL is as follows: https://download2.equ8.com/v1/a1/{id}/updates.json, where {id} is a unique identifier for the game (e.g. 36 for Splitgate)

This response can be parsed with the following structures:

We can then search for the anticheat.x64.equ8.exe file which is the main executable and download it.

FACEIT

FACEIT is the anticheat of private leagues for games such as CSGO or League of Legends. They are one of the top anticheats in this space due to their invasive checks and little public information about their detections.

You can find the download link on their anticheat page which links to here: https://anticheat-client.faceit-cdn.net/FACEITInstaller_64.exe It only includes the frontend iirc, and I didn't spend much more time on it.

ESEA

This anticheat requires you to have an account, and last time I checked their download page had a CAPTCHA, making it a little bit more inconvenient to track updates. Anyways, here's the download link: https://play.esea.net/index.php?s=downloads&d=download&id=1